gymnosperm plant

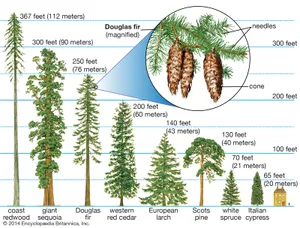

The term gymnosperm (“naked seeds”) represents four extant divisions of vascular plants whose ovules (seeds) are exposed on the surface of cone scales. The cone-bearing gymnosperms are among the largest and oldest living organisms in the world. They dominated the landscape about 200 million years ago. Today gymnosperms are of great economic value as major sources of lumber products, pulpwood, turpentine, and resins.Conifer stems are composed of a woody axis containing primitive water- and mineral-conducting cells called tracheids. Tracheids are interconnected by passages called bordered pits. Leaves are often needlelike or scalelike and typically contain canals filled with resin. The leaves of pine are borne in bundles (fascicles), and the number of leaves per fascicle is an important distinguishing feature. Most gymnosperms are evergreen, but some, such as larch and bald cypress, are deciduous (the leaves fall after one growing season). The leaves of many gymnosperms have a thick cuticle and stomata below the leaf surface.The tree or shrub is the sporophyte generation. In conifers, the male and female sporangia are produced on separate structures called cones or strobili. Individual trees are typically monoecious (male and female cones are borne on the same tree). A cone is a modified shoot with a single axis, on which is borne a spirally arranged series of pollen- or ovule-bearing scales or bracts. The male cone, or microstrobilus, is usually smaller than the female cone (megastrobilus) and is essentially an aggregation of many small structures (microsporophylls) that encase the pollen in microsporangia.

The extant cycads (division Cycadophyta) are a group of ancient seed plants that are survivors of a complex that has existed since the Mesozoic Era (251.9 million to 66 million years ago). They are presently distributed in the tropics and subtropics of both hemispheres. Cycads are palmlike in general appearance, with an unbranched columnar trunk and a crown of large pinnately compound (divided) leaves. The sexes are always separate, resulting in male and female plants (i.e., cycads are dioecious). Most species produce conspicuous cones (strobili) on both male and female plants, and the seeds are very large.

The ginkgophytes (division Ginkgophyta), although abundant, diverse, and widely distributed in the past, are represented now by a sole surviving species, Ginkgo biloba (maidenhair tree). The species was formerly restricted to southeastern China, but it is now likely extinct in the wild. The plant is commonly cultivated worldwide, however, and is particularly resistant to disease and air pollution. The ginkgo is multibranched, with stems that are differentiated into long shoots and dwarf (spur) shoots. A cluster of fan-shaped deciduous leaves with open dichotomous venation occurs at the end of each lateral spur shoot. Sexes are separate, and distinct cones are not produced. Female trees produce plumlike seeds with a fleshy outer layer and are noted for their foul smell when mature.

The gnetophytes (division Gnetophyta) comprise a group of three unusual genera. Ephedra occurs as a shrub in dry regions in tropical and temperate North and South America and in Asia, from the Mediterranean Sea to China. Species of Gnetum occur as woody shrubs, vines, or broad-leaved trees and grow in moist tropical forests of South America, Africa, and Asia. Welwitschia, restricted to extreme deserts (less than 25 mm [1 inch] of rain per year) in a narrow belt about 1,000 km (600 miles) long in southwestern Africa, is an unusual plant composed of an enormous underground stem and a pair of long strap-shaped leaves that lie along the ground. The three genera differ from all other gymnosperms in possessing vessel elements (as compared with tracheids) in the xylem and in specializations in reproductive morphology. The gnetophytes have figured prominently in the theories about gymnospermous origins of the angiosperms.

Angiosperms

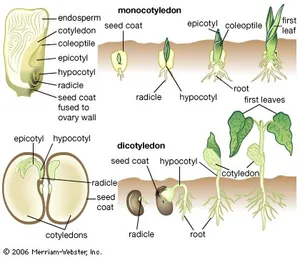

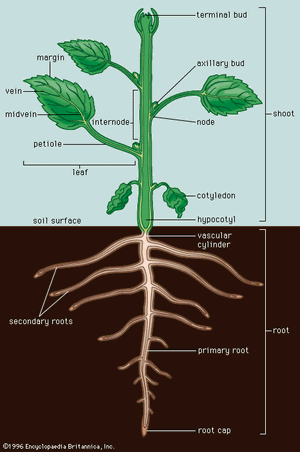

Approximately 130 million years ago, flowering plants (angiosperms) evolved from gymnosperms, although the identity of the specific gymnospermous ancestral group remains unresolved. The primary distinction between gymnosperms and angiosperms is that angiosperms reproduce by means of flowers. Flowers are modified shoots bearing a series of leaflike modified appendages and containing ovules (immature seeds) surrounded and protected by the female reproductive structure, the carpel or pistil. Along with other features, angiospermy, the enclosed condition of the seed, gave the flowering plants a competitive advantage and enabled them to come to dominate the extant flora. Flowering plants have also fully exploited the use of insects and other animals as agents of pollination (the transfer of pollen from male to female floral structures). In addition, the water-conducting cells and food-conducting tissue are more complex and efficient in flowering plants than in other land plants. Finally, flowering plants possess a specialized type of nutritive tissue in the seed, endosperm. Endosperm is the chief storage tissue in the seeds of grasses; hence, it is the primary source of nutrition in corn (maize), rice, wheat, and other cereals that have been utilized as major food sources by humans and other animals.

Approximately 130 million years ago, flowering plants (angiosperms) evolved from gymnosperms, although the identity of the specific gymnospermous ancestral group remains unresolved. The primary distinction between gymnosperms and angiosperms is that angiosperms reproduce by means of flowers. Flowers are modified shoots bearing a series of leaflike modified appendages and containing ovules (immature seeds) surrounded and protected by the female reproductive structure, the carpel or pistil. Along with other features, angiospermy, the enclosed condition of the seed, gave the flowering plants a competitive advantage and enabled them to come to dominate the extant flora. Flowering plants have also fully exploited the use of insects and other animals as agents of pollination (the transfer of pollen from male to female floral structures). In addition, the water-conducting cells and food-conducting tissue are more complex and efficient in flowering plants than in other land plants. Finally, flowering plants possess a specialized type of nutritive tissue in the seed, endosperm. Endosperm is the chief storage tissue in the seeds of grasses; hence, it is the primary source of nutrition in corn (maize), rice, wheat, and other cereals that have been utilized as major food sources by humans and other animals.

Classification of angiosperms

Many of the flowering plants are commonly represented by two basic groups, the monocotyledons and the dicotyledons, distinguished by the number of embryonic seed leaves (cotyledons), number of flower parts, arrangement of vascular tissue in the stem, leaf venation, and manner of leaf attachment to the stem. However, one of the major changes in the understanding of the evolution of the angiosperms was the realization that the basic distinction among flowering plants is not between monocotyledon groups (monocots) and dicotyledon groups (dicots). Rather, plants thought of as being “typical dicots” have evolved from within another group that includes the more-basal dicots and the monocots together. This group of typical dicots is now known as the eudicots, and molecular-based evidence supports their having a single evolutionary lineage (monophyletic). Other angiosperm groups, such as the Magnoliids, do not fit the traditional paradigm of monocot and dicot and are considered to have more-ancient lineages.

Stems